Rare Disease Day 2021 blog: West syndrome – a rare epilepsy as seen through the eyes of a father

Dr Charles Steward (pictured) is the Patient Advocacy and Engagement Lead at Congenica. He is also a member of the Participant Panel at Genomics England and the Simons Searchlight Community Advisory Committee, USA.

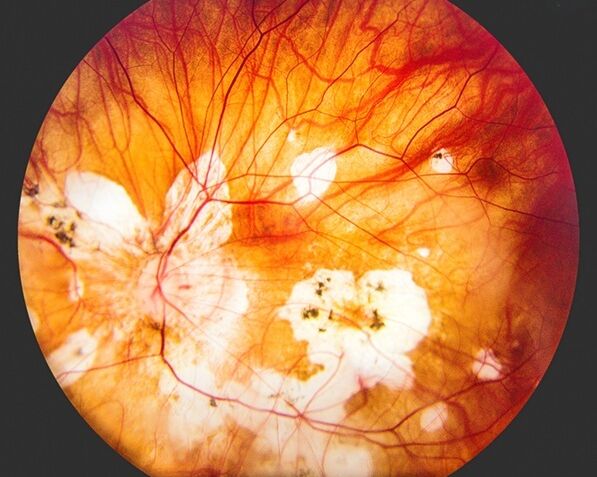

My daughter was born prematurely and at around 8 months old, she seemed to regress in her development and started making strange jack-knife movements at certain times of the day. She was diagnosed at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge with a rare and severe form of epilepsy called West syndrome. West syndrome diagnosis is based around the child having very specific and irregular brainwaves, developmental regression and seizures. Luckily, our clinician was actively involved in a clinical trial for treating West syndrome. She was enrolled in the clinical trial and within 24 hours, her seizures had stopped. This meant that she began to develop again, maybe not at the rate that other children her age would, but at least to some degree. My daughter also has severe cerebral palsy and is unable to stand. Receiving such news as a parent is devastating and you begin to look into ways of gaining control over these life-changing disorders. As a genome scientist, I jumped at the chance for my daughter to be enrolled into the 100,000 Genomes Project to look for answers to her challenges.

I have spent my 27-year career working on the human genome. I currently work at Congenica, a digital health company based on the Wellcome Genome Campus near Cambridge UK. Congenica develops software for health professionals to investigate the genomic basis of rare diseases, enabling rapid and accurate interpretation of complex genomic data to transform people’s lives. Congenica is also the exclusive rare disease clinical decision support provider, working in partnership with Genomics England to support the NHS Genomic Medicine Service to identify mutations in the genome which may cause a patient’s illness. I currently lead Congenica’s Patient Advocacy and Engagement programme, which means that my role is to help patients and clinicians understand the power of genomic medicine, but also its limitations.

I have a professional relationship with Genomics England, but I also have a very personal relationship too, through my daughter. I understand the challenges involved in finding information about rare diseases as I have spent many hours reading up on West syndrome. Something I read that was particularly interesting to me, as a father, was about the origin of the term 'West syndrome'. West syndrome was first described in the 19th century by a GP called Dr William West, who wrote about it in the Lancet in 1841. William’s son, James, was 4 months old when he presented with West syndrome. William wrote an impassioned plea for help:

Sir: I beg, through your valuable and extensively circulating Journal, to call the attention of the medical profession to a very rare and singular species of convulsions peculiar to young children. As the only case I have witnessed is in my own child, I shall be grateful to any member of the medical profession who can give me information on the subject … just before [the seizures] come on he is all alive and in good motion, making a strange noise, and then all of a sudden down goes his head and upwards his knees; he then appears frightened and screams out…

The language sounds archaic, but the message is very clear – this is a clinician looking for advice, but mostly it’s the voice of a very scared father looking for help for his son’s illness. This may have occurred around 180 years ago, but I can understand how he felt. James ended up in the Earlswood Asylum for Idiots in Redhill, which, to me, sounds a very frightening place, although subsequent reading suggests that the patients were treated with kindness. It is a quirk of history that the Medical Superintendent that oversaw James was Dr John Langdon Down who worked there from 1855 – 1868. Dr Down was the first person to describe Down syndrome. Interestingly, West syndrome is believed to be the most prevalent form of epilepsy in people with Down syndrome. William West died at the age of 55 in 1848, while James died at the age of 20 in 1860 of tuberculosis. They are both buried in the same grave in St. Peter and St. Paul’s Church in Tonbridge, UK.

Ultimately, the person we have to thank for the 100,000 Genomes Project is the ex-Prime Minister of the UK, David Cameron. As many people may know, David Cameron’s son, Ivan, was affected severely by a very rare and serious form of epilepsy called Ohtahara syndrome. Ivan also had severe cerebral palsy and tragically died at the age of six years. The struggles that Ivan went through and those that my daughter experiences means that Ivan is never far from my mind.

Ohtahara syndrome was first described by Professor Shunsuke Ohtahara in 1976 and is the earliest type of the age-dependent epilepsies, where the epileptic electrical discharges during seizures may contribute to massive brain dysfunction. Ohtahara syndrome generally occurs within three months of birth, but there are some accounts of mothers who have experienced their child having seizures in the womb. Professor Ohtahara proposed that there were three forms of age-dependent severe epilepsies that are somehow linked – Ohtahara syndrome, West syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is a type of epilepsy that occurs in children after the age of two and was first described in 1966.

It is interesting to note that children with Ohtahara syndrome may go on to develop West syndrome and they in turn may develop Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. All can be defined by the seizure type, specific brain wave pattern and developmental regression or stagnation. When my daughter was two, she developed a very different type of epilepsy to West syndrome, which I immediately feared was Lennox-Gastaut syndrome because of the age of onset and the links with West syndrome. Further investigations proved it was not, for which we were thankful, but the unpredictability of epilepsy is, nevertheless, frightening.

A syndrome is a group of signs and symptoms that occur together and characterize a particular abnormality or condition. All three of these syndromes, therefore, have similarities, both collectively and independently. However, we now know that the underlying causes of these related epilepsies can be genetic, due to brain injuries, and many other factors. As such, within each group, seizure types can be quite different, for example, West syndrome seizures can be as mild as the flickering of the eyes, to the more dramatic jack-knife movements. Such differences are clearly a result of different underlying causes. Genomics is beginning to help us understand this by identifying genes that are causative for these epilepsies.

The 100,000 Genomes Project is so important because the more people we sequence, the more chance we have to find the rare variants responsible for these disorders and the more we can learn about rare diseases in general. This will ultimately help to drive research into targeted therapies based upon the underlying cause. Even when there is currently no disease modification therapy available, a genomic diagnosis can help inform on appropriate recurrence counselling for parents, as well as allowing families to meet other families who have the same condition and help drive research – the voice of the patient is incredibly powerful! It can also help with bringing about psychological closure.

Currently, we can find the underlying genetic cause in around half of epilepsies. West syndrome is more challenging to find a cause when there are no other clues, for example brain injuries, so there is still some work to be done. However, there is one cause of West syndrome that, as a scientist, interests me particularly called tuberous sclerosis, a rare genetic disease caused by mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. It is possible to get a genetic diagnosis in around 90% of patients in such cases. It is also interesting to note that one of the precision medicines available that is guided by an understanding of the underlying genome is everolimus, which is particularly effective at treating tuberous sclerosis. Everolimus is a truly precision anti-epilepsy drug, because, unlike traditional anti-epilepsy drugs, which are administered without any knowledge of the patient’s underlying genome, everolimus targets specific genes and pathways, including TSC1 and TSC2. This is the future of genomic medicine and while we are still at the early stages for developing gene-specific therapy, we have a great foundation to build upon and accelerate such techniques into the clinic.

Dr William West died never knowing the underlying cause of his son’s epilepsy and clearly loved him dearly. Even 20 years ago, a great majority of children would have had no diagnosis for their epilepsy. Yet, thanks to projects such as the 100,000 Genomes Project and the work that Congenica is doing, we are seeing a huge acceleration in the ability of genomic medicine to change the lives of those people living with rare diseases for the better. Had James West been born in the past couple of decades, he and his family would have benefited from the modern medicines that treat West syndrome and perhaps been able to draw comfort and support from a genomic diagnosis.

My daughter is still waiting for a positive result from the 100,000 Genomes Project. So far, nothing has been found. Subsequent to my daughter’s enrolment into the 100,000 Genomes Project, our son was born three months prematurely and sadly, he suffered extensive brain damage during birth. He, too, has severe cerebral palsy and has also had his genome sequenced. Nothing has been found yet to account for their challenges. However, there is still a huge amount we don’t yet know about the human genome, so as new technologies evolve, I am very confident that one day soon, my family’s mystery will be resolved!

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr Alasdair Parker, Consultant Paediatric Neurologist at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge UK, Associate Lecturer at the University of Cambridge, and President of the British Paediatric Neurology Association for his help with this article. Dr Parker is the clinician who diagnosed and successfully treated our daughter for her West syndrome. He also supported us when our two-month-old son was diagnosed with catastrophic brain damage in NICU around Christmas 2017.