The Clinical Variant Ark at Genomics England

By Cassandra Smith, Chris Boustred and Ciaran Campbell onGenomics England stores a lot of data – both genomic and clinical. Over 100,000 whole genomes were sequenced through the 100,000 Genomes Project, with 2,000-3,000 now being routinely sequenced each month as part of the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS).

On the rare conditions side, this consists of tens of thousands of families, each of whom have their genomes analysed through our interpretation pipeline. The results of these analyses are interpreted by highly trained clinical scientists working in the NHS Genomic Laboratory Hubs (GLHs).

Genomic and clinical data can be powerful beyond a single family. For example, when deciding if a particular genetic change might be causing someone’s condition, it can be useful to look at other families where the same change has been identified.

Building the Clinical Variant Ark

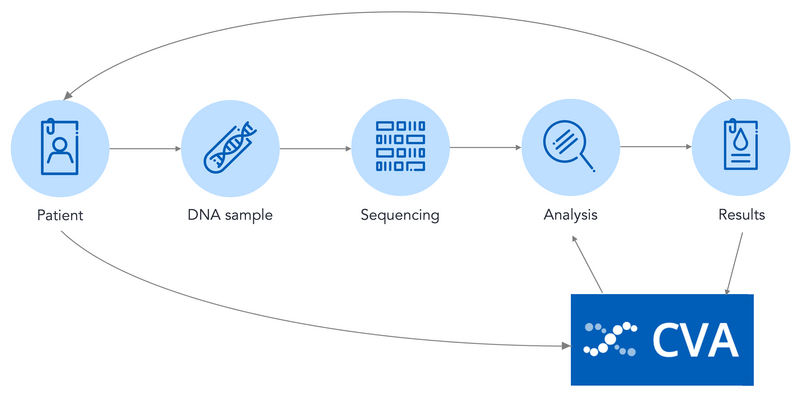

To maximise the power of all the data we hold, we built the Clinical Variant Ark (CVA) - a curated database (or knowledgebase) of genetic, diagnostic, and clinical information of families affected by rare conditions from both the 100,000 Genomes Project and the GMS. NHS users from across the country can access the CVA either through a web portal or programmatically through an API for more complex queries.

Data from all participants is loaded into the CVA, including a summary of the phenotypic features (described using Human Phenotype Ontology terms), applied virtual gene panels, and small variants that were highlighted (tiered) by the pipeline. For more information about this, see the guide on the rare disease pipeline at Genomics England.

The CVA also contains the results of interpretation by NHS clinical scientists. These results include the summary assessment for a variant (i.e. was this variant considered pathogenic), as well as all applied criteria as defined by the ACGS (The Association for Clinical Genomic Science). Guidelines are set by the ACGS for the clinical interpretation of WGS data to reach that conclusion, and free text fields where the clinical scientist who interpreted the variant can explain their reasoning.

As well as being able to search for specific families, it is possible to search for genetic variants, genes, or a wide range of other clinical or genetic features. Learn more about how the Genomics England bioinformatics pipeline prioritises potentially diagnostic genetic variants in the previous blog; Improvements to automated variant interpretation.

This means that once a variant has been assessed in a family by a clinical scientist, it is possible for others across the country working on different families with the same genetic change to identify this and take it into account in their assessment.

Analysis of future families through our rare disease bioinformatics pipeline also uses this information to increase the review priority of variants that have been assessed as potentially damaging previously, through a process known as known pathogenic variant prioritisation (KPVP).

The CVA takes data from across the sequencing and diagnostic process, and the data in the CVA is then used to guide future diagnoses.

Using the CVA for diagnostic discovery

Diagnostic Discovery at Genomics England focuses on uncovering putative new diagnoses for the participants of the 100,000 Genomes Project and patients sequenced through the NHS GMS. This diagnostic discovery work uses the CVA and supports new analysis by NHS clinical scientists.

Our knowledge of which variants might be associated with a rare condition (known as ‘pathogenic’ variants) increases over time. To make use of this improving knowledge, we wanted to identify variants assessed as pathogenic in at least one family in the CVA, and find other families where that variant was also present. This could uncover cases where previously there may not have been enough evidence to make a diagnosis.

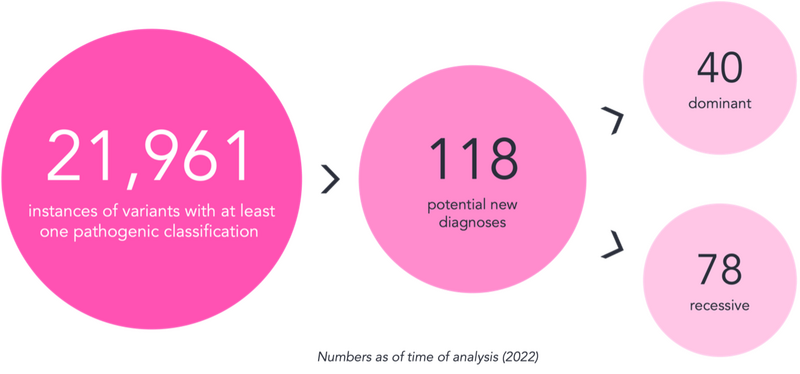

We wrote a script to carry out this search, which resulted in an output with over 20,000 lines. Each line contained information on a variant alongside the family it was identified in. Clearly, from the large number, most of these were not going to be new diagnoses.

So, what else needed to be considered when assessing these variants?

- Variants can be associated with conditions where only one copy of DNA is impacted (monoallelic or dominant) or where both copies of DNA must carry a change (biallelic or recessive). We checked that the variant(s) identified were consistent with the pattern expected for the relevant gene.

- Some variants show incomplete penetrance. This means that not everyone who has that change in their DNA will show symptoms of the associated rare condition. This is influenced by other genetic and environmental factors. We focused on variants associated with conditions that are related to the clinical question in the family.

- Just as increased evidence over time can lead to a variant becoming classified having uncertain significance. For example, access to more diverse datasets can show that a variant is more common than was previously thought. We considered any available new information when assessing these variants.

The output was reviewed with these considerations in mind, leading to the identification of 118 new potential diagnoses – 40 associated with dominant conditions and 78 associated with recessive conditions. These findings were returned to the NHS Genomic Laboratory Hubs for expert review through the Diagnostic Discovery pathway, highlighting the power of the knowledge in the CVA.

To read more about the work happening at Genomics England, check out the other bioinformatics blogs on our website.